Bring Your Own Buttons

Soviet Clothing and Creative Consumer Strategies in the Post-Stalin Era, 1953-1960

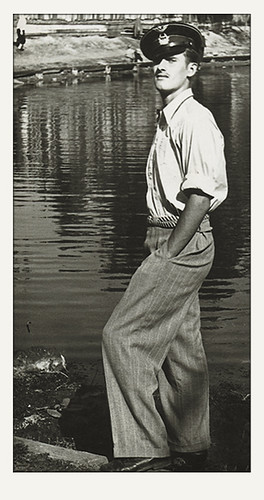

All Peter Gromov wanted was to buy a jacket for his bride. At Krasnodar’s main department store in 1955, he approached the sales counter with this simple request. The saleswoman happily obliged, spreading several jackets before him on the counter. Gromov gazed upon his options and, aghast, blurted out “I don’t like these.” The saleswoman hurried to mollify him by offering other styles—one with “zigzag seams against a dark background” stood out—but Gromov only became more distressed. “His heart thirsted for beauty,” the article in Pravda rhapsodized, “and on the counter lay its opposite—knitted jackets in ugly, dismal colors, inelegant patterns, careless finishing.” Dejected, Gromov left the department store, and decided to go straight to the authorities—the territory wholesale of the Chief Clothing Trade Administration. Surely they would have a solution.

When Gromov finally got an audience with the director, he “asked to see some good knitted garments,” upon which the director “smiled mysteriously and took an elaborately printed magazine entitled Trikotazh out of a desk drawer.” From among its pages, “stylish blouses and dresses, elegant suits and comfortable dressing gowns flashed before the charmed Peter.” Soon enough, though, Gromov became uneasy, and confided to the director, “But this is only a magazine.” The director, unfortunately, concurred. Gromov left the Chief Clothing Trade Administration, and walked home in a fog of disappointment. Suddenly, though, through the fog, Gromov noticed a wonderful jacket on the girl in front of him. “Just like the one in the magazine,” he thought to himself. “Tell me, where did you buy that?” he asked the unfamiliar girl. “Buy it?” she scoffed. “Klara Kuzminichna knitted it for me. I can give you the address. It’s all very simple. Just buy two [jackets] of different colors, unravel them and…” Finally, Gromov had found his solution. But although he had searched and searched within the state’s emporiums of consumer goods, he found the beauty his heart thirsted for not in stores, but on the street.

Gromov’s story, published in a 1955 issue of Pravda, is revealing. His wholesale rejection of the saleswoman’s proffered wares indicated the pragmatic chasm between his desire for “beauty” and the opportunities available for its procurement within the stilted consumer goods industry. His simple dismissal of the available jackets—“I don’t like these”—revealed the extent to which selecting consumer goods, for oneself or others, was an act of conscious consumerism—one in which preferences held implications for identity. Gromov’s interaction with the director of the Chief Clothing Trade Administration became a comedy of errors, in which the figure allegedly responsible for distributing good fashion and cultured, beautiful wares to the public ended up having power only over the idealized images portrayed in a printed magazine. And finally, Gromov’s encounter with the stranger on the street recounted a strategy frequently employed in the pursuit of attractive clothing: the creative adaptation and augmentation of available goods to match the unmet ideals of fashion promised so alluringly by Soviet publications. Confoundingly, these publications remained eager to educate their readers in the finer things of life—even when those finer things went unmanufactured and unstocked by the very factories and department stores responsible for their distribution.

Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953 ushered in a new era of consumerism in the Soviet Union. Georgy Malenkov—who briefly occupied the position of First Secretary, from Stalin’s death in March until being displaced by Khrushchev in September—presented a new, consumer-focused economic program at a session of the Supreme Soviet in August 1953. “The heart of it,” according to historian Elena Zubkova, was “the idea of reorienting the economy from the priority of heavy industry to the priority of consumer goods…converting even heavy industrial enterprises to at least partial production of goods in popular demand.” Khrushchev maintained this course, and raised “the issue of the poor quality and lack of variety of consumer goods…beginning in 1954.” This era of relatively exuberant consumerism was marked by ambitious promises and persistent disappointment, both of which played out dramatically in the Soviet press machine. During the 1950s, newspapers such as Izvestia and Pravda staged dialogues among producers, consumers, and retailers, in which consumers aired complaints and factory directors placed blame for shortages at arm’s length. These dialogues, while they had little effect on the actual production processes, had huge ramifications for the expectations of Soviet consumers—propagating high consumer expectations by acknowledging when they were not met.

The Soviet government was deeply invested in at least appearing to be responsive to consumer demand. This, too, marked a shift from Stalin’s policies. “After 1953,” according to Zubkova, “the mass media began to show increased interest in readers’ feedback.” Some publications “began to reserve special columns for the publication of readers’ letters.” All in all, “newspapers and magazines cultivated a more engaging style,” and placed “a new emphasis on audience differentiation and feedback mechanisms in print and broadcast media.” Operating under the limitations of a command economy in which quotas were king, factory officials, directors of fashion institutes, and department store managers settled for “responding” to consumer demands in the very most basic and inconsequential sense: they replied to consumers’ written complaints by writing back.

The “complaint economy” created by this exchange shifted the burden of demand fulfillment onto the consumer himself. Catriona Kelly has argued that this shift led to creative extralegal strategies. As long as “Soviet industry remained notoriously deficient in terms of the quantity and the quality of its output…the result, as everyone knows, was a mushrooming of the ‘shadow economy’, and of a substantial black-market trade in Western goods and scarce Soviet items, plus a boom in corruption.” However, stories such as Gromov’s and countless others published within the pages of Soviet newspapers after 1953 reveal a set of creative legal coping strategies. Although the shadow economy and corruption were two aspects of consumer response, consumers also seized the opportunity to pursue the sanctioned avenues of recourse offered by a more permissive government invested in keeping alive the dream of an achievable “good life.”

Using these strategies, consumers and retailers were able to adapt and augment state-produced goods in pursuit of visions manufactured by the state and unfulfilled by factories.

Soviet consumers persistently refashioned their world in the image of the idealized reality depicted in the propagandistic press. Many of their efforts were quite ambitious: some, like Gromov’s mysterious stranger, deconstructed existing articles of clothing and adapted them to suit more fashionable silhouettes; a few even performed “raids” on clothing factories they found unsatisfactory. Others expressed their dissatisfaction more quietly, by seeking out fancy ribbons, clasps, and other notions to augment dull state-produced goods. But beyond these tactics, many consumers chose to vocalize their disappointment in their local newspapers. Such acts of expression in fact constituted creative, legal coping strategies in themselves...

* * *

Previously:

2 comments:

I read this a couple days ago, but am too lazy to e-mail you. I would like to read the whole paper, but, as you can see, I understand if you, in turn, are too lazy to e-mail it to me.

Blargh. Poor writing on my part, but not on yours. "Rhapsodizing"=favorite word.

Post a Comment